H is for Hermanism

- Richard Ellis

- Feb 27, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 19, 2024

Hi, my name is, what? My name is, who?

My name is, chka-chka.... Harmenszoon?

So yeah. This whole blog thing could have been named "H is for Hermanism" instead. Yet, it isn't. That is because, in 1576, Jacob decided to Latinize Harmenszoon to Arminius as a sign of his transition into being a student at Leiden University. Apparently, this practice was quite common in the mid-16th century. And now, because of Arminius's decision and random historical luck, we are all stuck with the soteriological term known as Arminianism (which I think is cooler than Herman, tbh)

Of course, this isn't all that exciting on its own, and you may already know this information. So, who really cares about a name, right? It's not like there's some deep hidden meaning behind the name Arminius? ... Is there?

Well, actually, there might be.

As many scholars like to point out, including Bangs, Stanglin, and McCall, Arminius's name goes all the way back to AD 9 to a Germanic Chieftain by the name of Arminius. Unfortunately, that is usually the extent of the information given to us by these scholars.

Yet, in W. Stephen Gunter's commentary on Arminius's Declaration of Sentiments, we are given additional information concerning the Latinization of Arminius's name. Gunter writes:

"The common practice was simply to Latinize the father's name, so Arminius could have simply been known as Hermanni. His choice to use "Arminius" was an explicitly polemical act. The original Arminius had been a first century Germanic chieftain who valiantly resisted the Romans- certainly an inspiring persona for a young student whose family had been massacred by the soldiers of "Rome." (p. 13)

So, in this case, it seems as if Gunter thinks Arminius's name change was rather significant to Arminius's character. Unfortunately, Gunter doesn't offer us a citation for this information, and after googling the name Hermanni, the most I could find (after about five minutes) was that Hermanni was the Finnish form for the name Herman. See behindthename.com.

Fortunately for Gunter, me googling Hermanni for five minutes doesn't actually constitute real scholarship. Therefore, Hermanni could be a Latinized form of Herman. I just don't know. Likewise, even if Gunter is wrong about Hermanni, there still may be some validity to what Gunter suggests, especially since he provides historical context for this conclusion by referencing the original Arminius and its potential connection to young Jacob and the Oudewater massacre- which if you didn't know, this was a tragic event in which Arminius's whole family was killed by a Catholic backed, Spanish led army (well, actually, only an aunt survived, but that's beside the point- see below for more information)

So, after probing Gunter's proposal a bit further, I think I've uncovered three possible explanations concerning Arminius's name change (Gunter's being one of them).

Of course, take what I am about to share with a grain of salt. Without further information, much of this will be a bit speculative- but what history isn't?

(If you have your own theories, I'd love to read about them in the comments below or you can email them to me at AisforArminianism@gmail.com)

Will the Real Arminius Please Stand Up

The first explanation, that is, the least exciting one, is that Arminius is the standard Latin form for the name Herman, and Arminius chose to Latinize his name to Arminius because of this fact alone. In support of this view is the context that Arminius was quite a popular name during the mid-16th century, due to the rediscovery of Tacitus's Germania, which documents the history of the first Arminius.

As you can imagine, with the first Arminius opposing Rome in Tacitus's story, this would catch the imaginations of the early reformers who would self-identify with this story and their struggles against the Roman Catholic Church.

As Peter S. Wells writes in his book "The Battle That Stopped Rome."

“Martin Luther was enmeshed in his own struggles with Rome, both over theological doctrine and over what he considered the right of Germans to manage their own church affairs independently of the powers in Rome. In his writings, he expressed admiration for Arminius and his deeds, crediting him as the savior and liberator of his people.” Thus, being inspired by Arminius, “Luther may have been the first writer to Germanicize the Latin name Arminius into “Hermann” …” (34)

Thus, with its ever-growing popularity as a name, and it being possibly Germanicized by Luther himself, I think it would have been quite natural for the young Jacob, steeped in the Dutch Reformation of the late 16th century, to have Latinized his name to Arminius for no other reason than it being the standard Latin form for Herman and because of its popularity.

But, in light of this information, the more exciting explanation, given by Gunter, is that Jacob would have known that the name Arminius was a symbol of both German liberty and the protestant struggle, and thus he would have chosen to Latinize it to Arminius versus Hermanni as a purely polemical act following the massacre of his family.

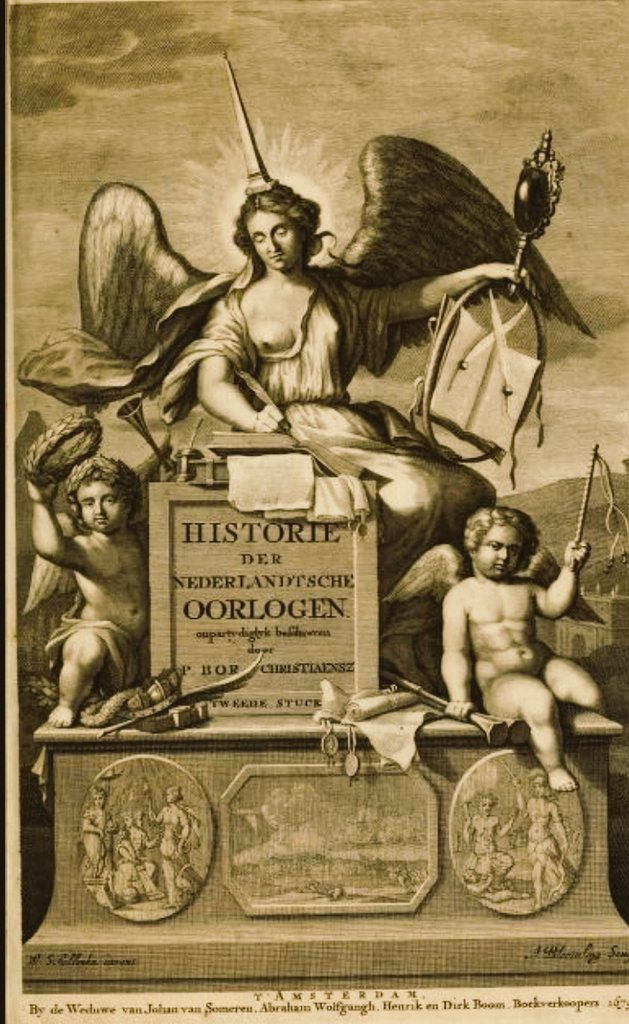

For those interested, the Oudewater massacre can be found in the respective works of Pieter Bor (Christiaenszoon) and Arnoldus van Duyn. That is: Oorsprongk, Begin en Vervolgh der Nederlandsche Oorlagen, 1555-1600 and Oudewaterse Moord.

As the story goes, Spain, who was considered Roman Catholic at this time, decided to attack North Holland. This of course, was not their first conflict. But on July 19th, 1575, with little to no warning, and no chance of escape, Gilles de Berlaymont, Baron of Hierges, launched an attack on the small, yet strategically and symbolically placed, town of Oudewater. He had an army of 11,000-foot soldiers, 15-companies of advance infantry, and 1,000-cavalry.

As Bangs notes:

“It is not a nice story. First the defending soldiers on the walls were shot or stabbed to death. Those who fled into the town were pursued and killed. Then the massacre spread to noncombatants. Mothers were killed in front of their children; children in front of their mothers. Girls and women were raped in view of fathers and husbands, and then all were killed. No place, no person, was exempt from the pillaging invaders. When nuns in the cloisters were discovered, they pleaded that they were faithful Roman Catholics. “So much the better for your souls,” said the soldiers as they raped and murdered them.” (pg. 41-42)

As you can imagine, this news would have elicited a strong emotional response from Arminius, and we have records that it did. As Petrus Bertius writes (this was Arminius's childhood friend) "...he [Arminius] was so much stricken at the heart and so greatly troubled, that he spent 14 whole days, in continual weeping and tears: Therefore as one impatient he left Hassia and went with speed into Holland, being determined either to see the ruines of his Country, or to loose his life.” Bangs also records that: “The town remained under the control of an occupying garrison until it was liberated again by Dutch troops under van Swieten, probably in December 1576. That means that when Arminius made his sad pilgrimage back to Oudewater, it was still in the hands of the enemy, which would account for Bertius’ saying that Arminius was determined to see his native city again “or die in the attempts.”” (43)

Thus, given the Oudewater context, the popularity of this name, and the emotional impact that this event had on Arminius life, Gunter's proposal, that Arminius's name change was done for purely polemical reasons, does seem substantiated by these stories.

Of course, you might think that Arminius was too soft or anti-divisive to choose such a name for polemical reasons. However, that isn't historically accurate. We know, both theologically and physically, Arminius was no push-over. Likewise, (regardless of how we interpret the following situations) documents do show that Arminius was not afraid to mock opponent's or call the pope an Anti-Christ.

In turn, I do think there is a third and better explanation for young Jacob's name change, and it is an amalgamation of the first two explanations above. In my opinion, Jacob chose to change "Harmenszoon" to “Arminius” because it was both the popular Latin form for Arminius and because Jacob knew that the name Arminius had an anti-Roman Catholic connotation associated with it. Therefore, given the chance, after the Oudewater massacre, I see no reasons against the idea of Jacob taking upon himself this "inspiring persona."

In all, we may never know Arminius’s true intent, unless there is some information out there that I don't know of yet (please share it if you have anything to add- truly I'd love to hear it). In the end, what is interesting, however, is how prophetic Arminius's name came to be. The first Arminius rebelled against Rome; Jacob Arminius rebelled against Rome by being a Reformed Protestant. The first Arminius was eventually hated and killed by his own people; Jacob Arminius was hated by his more Calvinistic peers prompting much controversy. Lastly, both seemed to have left a profound mark on history and the reformation.

Citations:

Bangs, Carl O. Arminius: A Study in the Dutch Reformation. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1985.

Stanglin, Keith D., and Thomas McCall. Jacob Arminius: Theologian of Grace. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Gunter, W. Stephen. Arminius and His Declaration of Sentiments: An Annotated Translation with Introduction and Theological Commentary. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2012.

Wells, Peter S. The Battle that Stopped Rome. New York, NY: Norton. 2004.

Bertius, Petrus, Funeral Oration on James Arminius. URL link HERE.

Comments